Oh the bemusing juxtapositions one gets when one's reading list is selected by a three-year old semi-randomly based on the cover. A few weeks ago my little Oprah picked out

James A. Garfield by Ira Rutkow ("Look, Daddy, it's Abraham Lincoln!" -- he recognized Garfield from the 'Presidents of the United States' place mat but couldn't quite place him),

Orbit by John Nance ("Hey Daddy, it's the space shuttle!"), and

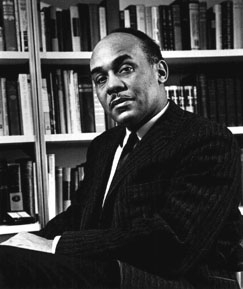

Ralph Ellison: A Biography by Arnold Rampersad ("Look! It's Daddy's friend!" referring perhaps to the statue of the Buddha Ellison is posing with on the jacket cover).

The Garfield biography is part of a comprehensive series of biographies of all the Presidents. One of the problems with a project like this is one gives equal shelf space to the administrations of Franklin Roosevelt and William Henry Harrison. You're stuck finding a biographer for all of them, and in Garfield's case, at the second shortest tenure among our chief executives, there's probably a good reason why there's a paucity of biographers. Garfield's chief achievement was to have died a lingering and probably medically unnecessary and excessively painful slow death after being shot by a whacko. So the editors of American Presidents tapped a medical historian to detail Garfield's life, and the result is unsurprisingly weighted a bit towards Garfield's agonizing and fairly disgusting final three months.

Now, being a fan of accounts of strange 19th-century medical practices and obscure Presidents, I have no objection to this, and I did learn a thing or two about the late President. (Disclaimer: as a callow youth in Cleveland, on occasion I was known to have partied on Garfield's grave, as well as frequenting the nearby and then-incredibly-disgustingly-cool collection of lancets, tumors in jars, and other pleasing medical memorabilia at the now sadly-modernized Dittrick Collection, which featured some of the instruments used to "treat" Garfield). Ironically enough, he was a believer in homeopathic medicine, which in the early first-do-no-harm school of thought, would probably have saved Garfield by leaving him the hell alone. But the "heroic" (read: medieval) school of medicine was employed on Garfield, largely because his cabinet made the decision as to which physician to put in charge of him (medical ethics and laws suggest this would not have happened in an earlier and certainly not a later age, when his wife would've made the decisions on this front), and the poking, prodding, and literally horse-manured handling of Garfield's wound in an unnecessary effort to get the assassin's bullet out gave Garfield multiple infections and finally blood-curdlingly (literally, perhaps) painful sepsis. What is especially disturbing is that the work of Dr. Lister concerning sterile environments and germs was well-known, widely practiced in Europe, but misapplied in the US. Comprehensive sterile practice was associated with medicine's younger generation, and in a guild-oriented system where some of the most senior practitioners had little formal medical training by current standards, time-honored practice and precedent was honored and practiced over the considered novelty of empirically-derived medical science. In a time when the scientific method as we understand it was still being developed, for those without an analytical approach to the human body, disease, and so forth, it was difficult to distinguish a genuine breakthrough from faddish quackery. So much the better reason to engage in time-honored quackery instead. So as a "compromise" position, some of the practices of sterile medicine were adopted with an obvious failure to look at the underlying cause and effect. In the specific case of Garfield, the surgeons would douse his wound with alcohol but introduced unsterilized hands and instruments directly into his wounds. And it was the senior (and therefore least knowledgeable) physicians who had charge of the system (and thrall over the US hospital system in general) by the very gravity and importance of the patient. The family were kept in the dark about his condition, the chief physician and the opposing homeopathic family physician fought battles over Garfield's care via the press instead of in medical conference with one another.

As for Garfield, this strikes one as a familiar story: raised by a single mother in poverty, he escapes his hick town through ambition, currying of favor, and natural talent to get to an elite Eastern college (in this case, Williams). In an age of open rapacious capitalism where government was viewed in very limited terms with respect to forging national prosperity but in the most open terms when it came to patronage and personal gain, our hero ascends the ranks through a combination of pluck, greed, good timing and back-slapping charm. Managing to make the most out of an 18-month military career in the civil war that started with a political appointment and ended up with a staff job that lead to a Congressional seat in the middle of the war, Garfield ascends through the ranks of Congress by being utterly affable and fairly unremarkable in terms of taking extremes on any issue. Along the way, he commits not a few infidelities to both spouse and country. He emerges from a brokered convention as a compromise moderate candidate, and takes an utterly corrupt Vice President whom he can't personally stand on as political deal as part of the nomination process. It's the all-American story! Only instead of ending with the puppy licking his face, Garfield ends up getting shot at by a delusional nut job who wanted to become ambassador to France and thought the less than luminary Chester A. Arthur presented a better opportunity than Garfield, who rejected him repeatedly (he was hanged, of course, instead of being committed.)

A couple more odd factlets I learned from this book: despite Lincoln's assassination, Presidents still had very light protection - Garfield walked by himself to the Capital building and various appointments, for example, and the assassin simply read his schedule in the paper and trailed him to the train station. Congressmen typically also picked up extra money as lobbyists in those days, Congressional pay not being enough to support a person in Washington, and Garfield as a practicing lawyer did all sorts of lobbying that would be shocking today (if done above board, at least). There was no revolving door - none necessary, as you could keep your seat in Congress, represent the robber barons, and still be re-elected by landslides because of your alleged war record.

Garfield himself comes across as likeable if arrogant in fairly recognizable ways. One gets the sense that he would've been a competent caretaker President had he survived, which is a favorable contrast to the Peter-Principle incompetence of the Grant and Hayes administrations and the execrable accidental Presidency of Arthur. (It's a sign of how prosperous the country was during the guilded age that the rampant corruption and general mismanagement seemed to have had a negligible effect on the overall commonweal, even if it was an egregious offense to certain segments of society, notably the freed slaves in the post-Reconstruction era.) If he's forgotten, it's probably because he was so much of the type that he wouldn't've been that memorable even had he lived.

One more footnote: I was a bit surprised at the description of the national mourning and keening over Garfield's death. Even if he was well-enough liked, he did not win the Presidency by much of a majority and his election and person still represented division in a country at internal odds with itself. Even his own party was disputation and divided: the nature of this schism in the Republican party played a role in the mindset of his assassin. But then one considers the nature of Garfield's death, played out by hourly telegraph bulletins and in broadsheets over an extended period. The media hasn't changed much here, either, considering the coverage of celebrity deaths and cute missing persons in exotic locations. If Garfield weren't as well loved as the noting of his passing might have indicated, people had come to believe he was. Which is why there's a gigantic honking memorial tomb of him in Cleveland, and why nobody remembers who he was otherwise.

Orbit had all the earmarks of the kind of brain candy I normally find very amusing: an everyman hero who wins a trip into space on a private spaceship and who, after a freak accident kills the pilot, finds himself alone and on his own in orbit around earth with a broken spaceship and only five days of oxygen. It's the kind of story that Robert Heinlein should've written in the 30s or at least in his boy-science-fiction phase in the 50s. Alas, Orbit's hero isn't a plunky 12 year old but a middle-aged white guy on his second bad marriage, disrespected by his haraden of a wife and blamed by his eldest son for the untimely death of his psychologically unbalanced first wife, living vicariously while drudging away at a meaningless if well paid white collar job for the pharma industry and lusting secretly at the hottie PR director of the private space tourist company (who of course lusts after him, too). This wouldn't quite make it one of the worst, most self-indulgent pieces of crap I've ever read, but the implausible, techincally dubious, and extremely unsympathetic schtick that follows does. See, our hero, Kip, who is presented as a man of action, decides to write up his biography-cum-theory-of-life into the laptop that functions on the spacecraft, for the benefit of future generations fifty years hence when his body and the ship just might be recovered. The theory here is that no man is as free with his thoughts as the dying man, in this case literally free of the constraints of society, not even to mention gravity. Even though all his communications have been blacked out by the space junk impact that killed the pilot (but conveniently left the life support system and the laptop intact), there's one of those "backdoors" the author apparently read about (probably in the same report that Senator Stevens used to describe the giant Tubes on the Internet), linked up to a downlink that works but can only transmit information one way (are you following?) So what Kip thinks he's writing for posterity is actually being scrolled real-time on the internet thanks to an intrepid hacker-boy. Kip's honest truth-telling makes him an instant worldwide celebrity, and his screeds representing the poor oppression of upper class white guys in America become the inspiration for millions of ungrateful teenage boys to start respecting their dads, millions more uptight biatches of wives to start putting out for their husbands again, and for America to regain its faith in the promise of technological space over pussy-domestic politics as the true measure of its national masculinity. Oh, and then after he's spent five days spieling to the world, he suddenly figures out how to fix the spacecraft and land it all by himself, against all odds, of course, so he can return to earth and teach his eldest son how to flyfish, divorce that bitch of a wife he has, and swap fluids with the pliant PR director who's never really met a 44-year old man quite like Kip. While one might argue, in a different universe, how the abstractions of fiction, particularly putatively science fiction, ought not to be confused with autobiography, I'm fairly certain about how John Nance feels about issues such as the Carter Presidency (America's limp-wrist), Ginger vs. Marianne (Ginger), Don Imus vs. Larry King (Imus is a hoot, King's a long-winded bag of gas), government bureacrats (agin' 'em!), brave-hearted venture capitalists (for 'em!), and a number of other rather extradiagetic matters of zero national or fictional concern. To give credit where credit is due, the plotting at least had me reading to the end to find out the ultimate-if-predictable fate of our truthtelling hero. The theme of this book seems to be: if there's one segment of society that's ignored, it's the high-income middle-aged white male in the middle of the military-industrial complex. I would go so far as to say most self-published books are better at providing new voices.

Speaking of familiar stories voiced by the over-voiced, here's a familiar tale. Brilliant but misunderstood young man raised in poverty by a single mother knows he is an artist and is certainly smarter than everybody else around him and yearns to get out of his backwater provincial hometown. Thinking himself to be a great musician but torn between jazz and classical music (as represented by two very different teachers), he yearns to go to an elite educational institution where at long last people will understand him. Through hard work and perseverance, not even to mention quite a bit of talent, arrogance, ambition, and personal appeal, he manages to get to said college...only to arrive and find it to be a place of petty academic politics, anti-intellectualism, sexual hypocrisy, and tight-fisted failure to recognize his genius at whatever it is he might be doing. He sticks with it for years, miserable, and finally drops out to go to the big city -- New York City -- in order to make it big as an artist, except now he's decided he's a sculptor, not a musician. Eagerly falling in to the cocktail-party circuit of left-wing politics, he becomes a radical and accumulates a blue collar resume of short-term dead-end jobs even while becoming the darling of a certain segment of the radicals for what he represents much more so than who he actually is. Along the way he marries a fireplug, a woman with talents and ambitions that exceed his own, a relationship that of course falls apart under the weight of his own ego. Finally deciding that he's a novelist, not a sculptor or musician, he embarks upon a seven-year struggle to write the Great American Novel. Oddly, his talent and ambition and pretension and strange combination of self-taught mythology, literary criticism, and sweeping class history of the country actually produce something close to the Great American Novel. Parts of it leak out. Even as he's eating stale macaroni and cheese and fighting periods of homelessness, hints of its genius sweep across literary circles, and he is encouraged and then supported by a series of benefactors and foundations to finish the novel. Given a hefty advance, he then finds his perfectionism won't allow him to finish the book. He finds numerous ways to procrastinate when the writing, which doesn't come easy, doesn't go well: he takes up photography, he builds his own amplifiers at home, he obssessively makes coffee according to an exacting procedure. He seeks a teaching job only to reject it when it's offered to him. Years drag on as he works and reworks it under the respectful and supportive eye of his abused second-wife, who never will get the credit she deserves in the great book that follows. Along the way, the hero does a political one eighty and becomes a strong advocate of a progressive but mainstreaming approach to society's gravest ills. Finally the book gets published, not just to great acclaim, but to international acclaim. It's banned in Ireland and Boston as obscene, blamed for riots and the downfall of America's youth, while simultaneously being proclaimed as the voice of his people and generation by everybody except his people and generation. He wins prized and awards and becomes a sought-after board member, foundation director, guest commentator, lecturer, interviewee, et alia.

And there's the rub. He then spends the next four decades praised for his seminal first work, and completely unable to finish his second. Shades of the Great American Novel about Writing the Second Great American Novel (cf. Michael Chabon and Wonderboys, Richard Russo and Straight Man, etc.) His very success makes him the target for attack as a new generation of young writers comes along and attacks the bourgeois nature of the writer. As the years wear on, the accolades continue, as do the one-year teaching appointments, the special fellowships, the lecture appointments, even as his audience begins to wonder if he's really working on a second book after all. Is he blocked? Does he have the writer's affliction? No! He's working on a novel, after all -- and it's 2000 pages and counting and there's no end of it in sight. He ends his days surrounded by his manuscript, supported by his long-suffering wife, with prizes aplenty but an uncertain legacy.

OK, so this sounds not unlike the Bret Easton Ellis story thus far. But because it's Ralph Ellison's life, you have to introduce the fact Ellison was black, born into the worst era of Jim Crow and to what some consider to be the golden age of the American intellectual. The story is quite a bit more complicated as a result.

Still, the Ralph Ellison story can be told very simply in two acts: boy spends the first half of his life writing his first novel; spends the second half of his life not finishing his second novel. Part of Ellison's fascination for me has been this very fact that he managed to get one great novel out but tanked on another. Harper Lee (whether or not she actually wrote To Kill a Mockingbird is beside the point, perhaps), another case in point, seems not to have even tried. Ellison, having struggled to write a strangely beatnik book (IMHO) that is a funny and kind of surreal ride, was determined to write a topper. I'm actually fairly convinced that he had just made up his mind he was an Intellectual and a Novelist, having a thin skin and a huge ego, and was stuck living that out (shades of Vonnegut's dictum about we become that which we pretend to be.) Ellison, but all these accounts, was quite a brilliant thinker in his way but also thoroughly addicted to the canon, for better or worse. I've never read anything he wrote except Invisible Man and an excerpt of Juneteenth, which itself is a posthumously-edited excerpt of the 2000+ page unfinished second novel. What I did read in this biography seems distinctly of its time; a period when criticism was perhaps unduly respected, an attitude that resulted in a highly constructed novel but (to me at least) pretty stale non-fiction. God, what a name-dropper of a biography this is: every literary light of the mid-20th century in America (the alleged golden age of America's novel) is here someplace. Ellison's buddies with John Cheever, Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, the protege and then opponent of Richard Wright, the employee of Langston Hughes, the dinner mate of TS Eliot (whom he worshipped, but who probably loathed Ellison if he thought of him at all), and so on all the way up to Toni Morrison.

The kind of ur-tragedy of Ellison's life is his identification as a "black" writer (then: Negro; now: African-American). From what one gleans of Ellison's basic character, he would have done much better to have been born in a time where he would've simply been an American writer, or a writer, period. As such, with the racially-tinged and pseudo-autobiographical flavor of Invisible Man defining him, more was read into Ellison as a black writer than he was perhaps naturally willing to express on his own behalf. He struggled for a theme and a plot even for his first novel, practically taking notes from his wide reading, lectures he attended, dinner party conversations, and so forth. He had more natural love for Melville and Joyce and Eliot than for the writers he gets associated with in survey classes. Speaking as someone who read Ellison during the same summer I devoured William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, and discovered PK Dick, taken on face value I'd lump Invisible Manmore in that line than with Black Boy just on the experience of this reader. Of course, what one brings into reading a book in terms of life experience and cultural baggage has much to do with how one reads it, and the fact that, say, Burroughs and Kerouac are practically the only 20th century writers not dragged into this biography perhaps speaks to my bias here.

I have the distinct impression that had Ellison been born, say, fifty years later, he'd've ended up a perfectly well-liked and respected but obscure professor of English someplace, teaching Mark Twain and Jane Austen. If he'd been born, say, fifty years earlier it's unlikely he would've achieved what he did. He managed to squeeze a considerably articulate talent, if overly ambitious and, dare I say it, lazy one, into a window where because he was born African-American in the society he was born into, produced a life that was at once burdensome and strangely easy. To be brutal about it, one gets the impression that Ellison spent the last forty years of his life riding on his laurels -- which consist of one book -- at perhaps the only time in history when one could've gotten away with it. To take nothing away from his talents as a critic and lecturer and teacher, which no doubt were considerable. But it's equally hard to imagine the talented author of a single book today, regardless of his ethnicity, cultural background, or other descriptive characteristic, being able to make a career out of one book.

I dislike the biography-as-criticism. I read biography to live another person's life vicariously, and in turn, one hopes, to apply that to my own life, or at least be entertained by it, or at least to learn more about the times and life closed off to me. The problem with this book, or perhaps Ellison's life, is that I'm fundamentally uninterested in the fact that Ellison paid $10 to have his windows washed in 1954 or that a lot of his colleagues were sleeping with one another at the American Academy in Rome or that NYU had a mandatory retirement policy. It's a comprehensive biography, very scholarly, but after slogging through all 700+ pages I'm still left wondering at the essential question of Ralph Ellison's life, which to me is the second act. I find it unremarkable in a way that a talent such as his rose to the top despite the odds; I do find it remarkable that, if he really did think of himself as a novelist, he couldn't pull the trigger again, and mysteriously tragic that he couldn't reinvent himself otherwise except in the rather mainstream way he did.

Invisible Man: that was the book we didn't read in the "books by black authors that show up on the reading lists" back in school in the 70s. There's too much sexual content, strangely confusing and anachronistic racial commentary, bizarre imagery for a high school teacher (at least back then) to be able to accommodate. We got Black Boy (instead of, say, Native Son) and Mockingbird and maybe a little selected Maya Angelou because they lent themselves to teacher's guides, and fit into the then- (and possible still-) fashionable approach of solving the problem of the traditional canon by simply adding authors on to the traditional reading list and dropping out a few of the more boring and mostly dead white guys that had padded it out. Invisible is a more challenging book not the least because it's not really autobiography so much as a filter of Ellison's biography, and there's more meat to it in the long run, even if there's a lot more baggage to riffle through as well. That Ellison started out a Communist and ended up about as bourgeois as they come is another subtext one can read in the book, the fulcrum of his life, if we were going to stoop to reading subtexts. I still can't decide if Ellison was a talent that had to be wrung hard, or an opportunist, but in keeping with my self-professed attitude towards biographies, maybe I should just abandon Ellison the man and re-read Invisible Man. Literary biography, after all, isn't dessert, it's not even sauce, it's more of a place setting -- salad fork? -- that may be completely unnecessary if one has finger food and a ravenous appetite, not even to mention little regard for making a mess of one's face.